2021:8 Payments, market infrastructure, banks, creative destruction and Latin-America.

Time is flying when you are having fun - we are already in April!

2021:8 was created over multiple days (i.e. dropped something in here when I read something interesting) - a win efficiency wise. Also put some extra headline titles on each section - guess this make it easier to browse through.

Enjoy and feel free to reach out!

Payments

Some interesting overview publications with regard to payments:

Credit Suisse (CS) with a huge publication on payments, processors and fintech.

A JPM talk on the payment ecosystem.

Hayden Capital on Buy Now Pay Later.

I am a generalist in terms of companies - so I do like the overview of the different players in the value chain at the end of the CS publication:

When talking about a company - I feel it is always a good idea to draw these kind of industry overviews. An important point in terms of players imo is:

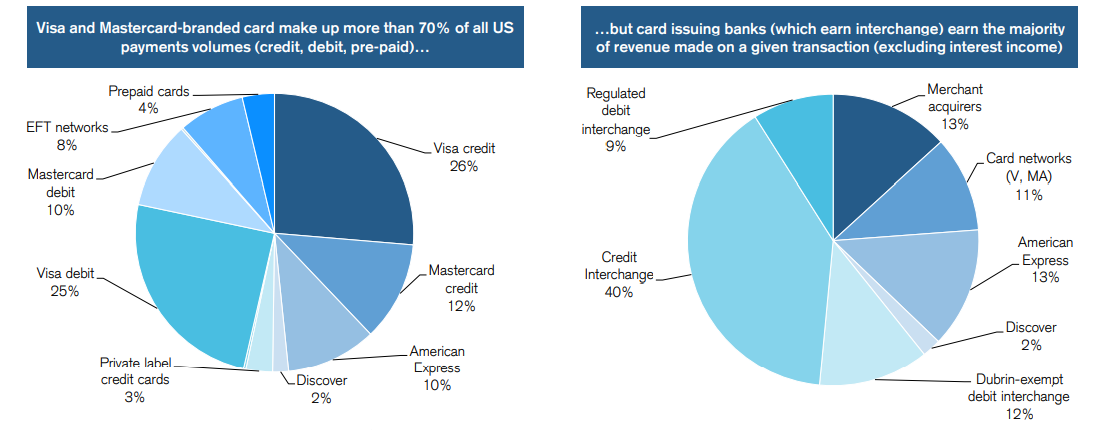

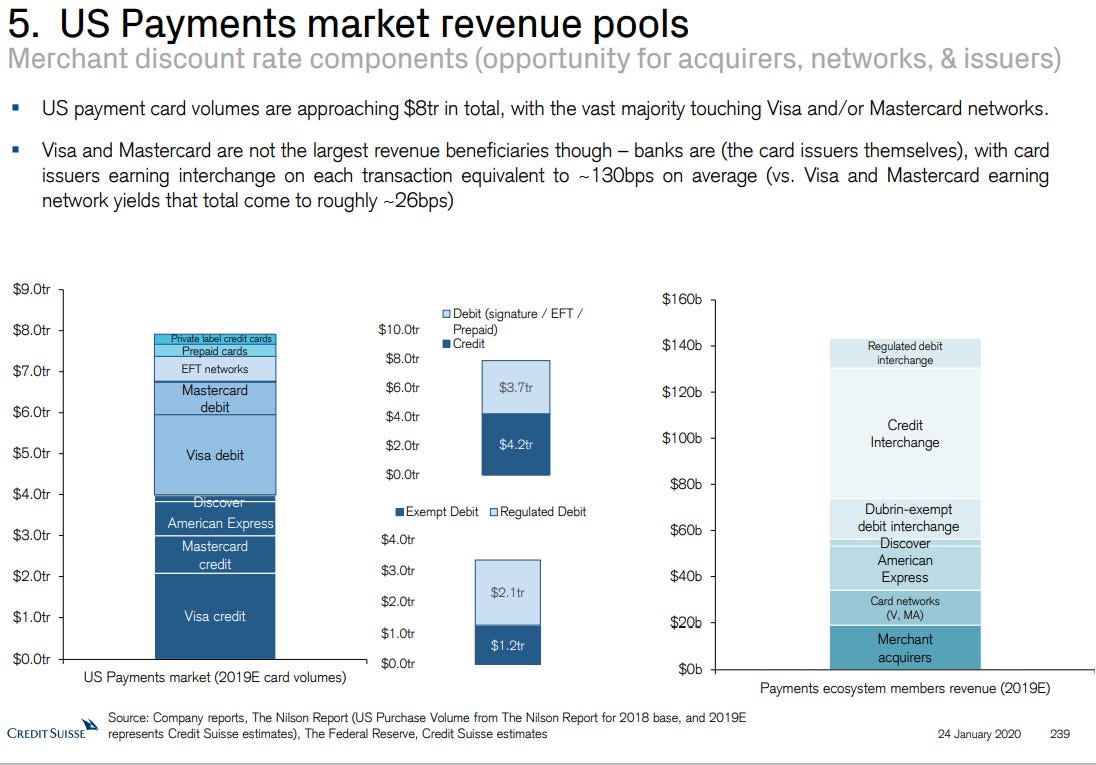

Visa and Mastercard networks are almost always involved

banks - the card issuers - still make the most money because of the level of interchange fees (depending on the country / regulation - picture below is for the US)

I found this overview of interchange fees on ValuePenguin - which has some other good reads on the topic as well. As you can see - big differences between countries:

Regulation - especially in Europe - pushed interchange fees down. An important detail here is also how the merchant acquirer charges: interchange ++ or blended. The first one is more transparent and allow the merchant to more clearly reap the benefits of declining interchange fees. The blended variant might be easier (just one “total” charge) but allows the merchant acquirer to take more if one component (interchange fees in this case) lowers (eg Square rack rate pricing). From Adyen’s blog:

Besides the industry overview - and specific company analysis in the middle part - there are also some general trends in there.

87% “un-carded” opportunity

SMB segment: 17% volumes but 55% revenue in US market

traditional (“brick on counter and/or large merchants contracted separately) will lose share against software-led (eg Square) and e-commerce

CS expects further consolidation among merchant acquirers:

The JPM talk is summarized by Secret Capital:

Hayden Capital published a piece on Afterpay - a BNPL company. Not really familiar with it but feel it is an interesting add to where the industry might go (or not go). Afterpay has a 5% take-rate and a 30% margin (looking at Australian operations - just looking at consolidated numbers hides this). Btw: again you see Visa and Mastercard popping up in this flowchart

Market infrastructure & payment for order flow

I enjoyed the Odd Lots podcast with Virtu CEO Doug Cifu.

Similarly A16Z had a good write-up on the topic recently.

If you don’t let retail brokers charge market makers a fee for the order flow, then retail brokers would still likely route orders to market makers in order to receive the better execution they provide to retail investors, but without this revenue stream, retail brokers may need to just raise fees on retail investors, and market makers would make more money.

Without routing to an “internalizer” or “wholesaler,” retail investors will likely face bigger spreads, less liquidity, and higher fees as everything would get routed to a costly exchange or alternative trading system when market makers couldn’t provide the better prices to retail.

SEC Rule 605 requires that market makers publish their execution stats every month. Looking at the recent data, it shows that wholesaling saves customers money—$3.57 billion of price improvement in 2020 alone.

Similar to for example a Flow Traders (quoted on Amsterdam) these kind of companies offer some kind of hedge in a volatile market environment (often when market goes down). Both Virtu and Flow Traders showed a 30% return in February/March 2020. No free lunch of course: in 2019 both significantly underperformed the broader indices.

Banks & industry profitability

Recently bank stocks got some renewed attention - mostly because of recovering share prices against the background of a recovering economy and higher rates (or a steeper yield curve). Still it is fair to say they still aren’t the most popular long term investment thesis to talk about. For Europe: a zero (gross) return for the MSCI Europe Banks over the last 10 years probably doesn’t help (for the record: MSCI USA Banks did much better with a 15% gross return per annum).

In general I guess the Munger quote “fish where the fish are” makes a lot of sense. Some industries simply have much better economics (as a whole and/or more than one company is taking a profitable share) and the pandemic seems to have accelerated this even more. From McKinsey:

What’s driving this widening chasm? So far, we aren’t seeing a great reshuffling of industries and companies along the power curve as was the case during the global financial crisis, when companies in the electronics, energy, and financial-services sectors fell off their historical peaks. Rather, industries and companies that started at the top of the curve before this crisis are proving to be resilient, while those that were at the bottom are accruing the biggest losses.

This increased dispersion can be seen both across and within industries. Sectors that were at the top of the curve before the crisis, such as pharmaceuticals and semiconductors, seem to be pulling ahead from the less profitable industries that started at the bottom, such as banks and utilities (Exhibit 2). In fact, the six most-profitable industries have added $275 billion a year to their expected economic-profit pool, while the bottom six have lost $373 billion.

This being said - I discovered Maxfield on banks who has some good Twitter threads on investing in banks and some good lessons in general:

1. Fortunes can be made in banking but only by earning consistent returns through multiple cycles. Banking isn’t a get-rich-quick business. There are graveyards full of banks that chased short-term performance at the expense of long-term solvency.

7. The suggestion that banks can’t evolve and innovate ignores centuries of evolution and innovation. The oldest bank in the United States was co-founded by Alexander Hamilton. It survived the Civil War, the proliferation of the automobile and the invention of the internet. This creates at the very least a rebuttable presumption that many banks will survive the digitization of finance.

9. An easy litmus test for any bank is how it performed through the latest crisis. Well-run banks embody the ideal of antifragility. They underperform by a little in good times but outperform by a lot when times get tough.

10. Highly efficient banks aren’t necessarily those with the lowest costs. The typical bank earns twice as much revenue as it pays out in expenses. So if a bank’s goal is to improve efficiency, expressed as a ratio of expenses over revenue, it’ll get twice the bang for its buck by increasing revenue relative to cutting costs.

12. Leverage is the friend of a good bank, enemy of the mediocre. Most companies are leveraged by a factor of three — borrowing $3 for every $1 in capital. The typical bank is leveraged by a factor of ten. This enables a bank to compound value at a rapid rate, but it also leaves little margin for error.

13. In banking, strategy matters less than execution. Some banks grow by paying a discount for troubled banks; others grow by paying a premium for well-run banks. Some banks prioritize dividends; others repurchase lots of stock. Some banks centralize risk management; others distribute it. There is no one “right” way to run a bank.

15. It’s the consistency, not the amplitude, of earnings that drives long-term value in banking. The first rule of compounding, Charlie Munger once said, is to never interrupt it unnecessarily. This is especially true in banking, where losses can snowball into acute shareholder dilution.

20. Success in banking is first and foremost about winning a war of attrition. More than 17,300 banks have failed since the birth of the modern American banking industry 160 years ago. That’s over three times the number of banks in business today.

Agony & ecstasy: creative destruction

JPM updated their Agony & ecstasy publication.

A really important point with regard to investing and business in general:

More than 40% of all companies that were ever in the Russell 3000 index experience a “catastrophic stock price loss” (defined by a 70% decline in price from peak levels which is not recovered”.

Around 40% of the time a concentrated position in a single stock experienced negative absolute returns, in which case it would have underperformed a simple position in cash. Around 66% of the time, a concentrated position in a single stock would have underperformed a diversified position in the Russell 3000 index. Only 10% of all stocks since 1980 met the definition of “megawinners”.

I see different takeaways from this kind of research. Some people want to go more diversified - others want to go even more concentrated and focus on picking the ultimate winners.

My takeaway is that:

some diversification is healthy if you see the stats above - know what you are up against (in terms of capitalism, cycles, creative destruction, other investors, fraud, you are still an outsider,…) ~ where that diversification ends exactly is of course up to your personal taste, believes and overall investment process (and end investor)

you should resist the temptation to sell a good company / business model after a small run

Latin-America

I am reorganising my newsfeed a bit. Keeping the John Authers newsletter because often there is an interesting graph or takeway in it. In his latest he picked up some UBS research on Latin-America:

Guess he is also subscribed to Capital Economics (the graphs regularly show up in his letter) - good reminder of the amount of stimulus the US is putting out there (note that the possible USD 2 trillion spend on infrastructure isn’t in here - this would add another 10%):

Enjoy!