2021:7 Nike/Adidas margins, intangibles accounting, inflation, shipping costs, paradigm shifts and Facebook offices

This week something about the big sportwear companies such as Nike and Adidas, the End of Accounting, another wrap-up with regard to inflation, Paradigm shifts and the new Oculus offices from Facebook.

Enjoy!

I was digging a bit in the sales and margin evolution of the big sportwear / athleisure companies:

Gross margins mostly circle around 50% of sales. Lululemon has the biggest mark-up here and recently realizes 56% gross margins.

Operating expenses are between 30% - 40% of sales.

To simplify: the average sporting shoe or sportwear you buy for EUR 100 has a cost basis of:

about EUR 50 direct costs / cost of goods sold (e.g. material and labor)

about EUR 35-40 indirect costs / operating expenses (e.g. advertising, marketing, IT and rent)

To be complete: R&D costs are negligible. And they still need to pay some interest and taxes of course. Let’s say making a shoe as such is quite profitable (50% gross margin) - but it takes a lot of (ads, marketing, sponsorships,…) money to make you buy it. As people sometimes say: “Nike is a marketing company that happens to sell shoes”.

To visualise this - look at the 62.000 employees of Adidas:

(Btw: Adidas outsources most of the production)

Adidas recently had an investor day where they explained their 2025 “Own the game” strategy. They want to reach Nike’s level of operating margins:

Was reading the End of Accounting (from Baruch Lev and Feng Gu). Not 100% what I was expecting - but a good reminder with regard to intangibles accounting:

The Mauboussin “One Job” is also a good recent publication on this issue:

In my previous post, I wrote something about inflation. It is clear that is a headline risk that is on people’s minds:

It will also be on the agenda of central banks this week:

John Authers (Bloomberg) decided it was time to write about it in his latest newsletter. Authers considers a monetary take on it:

That is what might be called the monetarist case for a return of inflation. Demographics and a healthier banking system will combine to ensure that the vast new quantities of money in the system move around much faster this time. It’s a convincing argument to be more concerned, and not to take the lack of inflation after the GFC as a guiding precedent. But it still requires a number of steps to fall into place in the future.

And a view from the commodity world - where he points to Capital Economics research which btw doesn’t believe in a new supercycle:

Another argument for secular inflation comes from commodity cycles. When commodity prices are rising, virtually by definition consumer inflation also rises as raw materials costs are passed on. Prices of industrial metals and particularly oil have turned up sharply in a way that looks very much like the start of a classic secular up-cycle (covered in Points of Return here).

The commodities team at Capital Economics Ltd. in London made an interesting attempt to douse down the hopes (or fears) for a prolonged upward trend in prices.

Commodities are a tricky business in the sense that:

price moves (up or down) are sometimes triggered by a small imbalance in supply and demand - coming out of the pandemic there might be a mix of demand and supply factors at play

higher prices often attract more capital and investment in capacity - this doesn’t come to market quickly of course (which historically sometimes made it worse i.e. more supply when demand was actually already in decline)

it remains to be seen which commodity prices are passed through by companies to consumers

In my previous post I showed a graph of M2/GDP - which visualises the increase in money supply and overall liquidity in the system. I feel most people use M2 - but nevertheless an interesting point by Morgan Housel (Collaborative Fund) on the definition change of M1:

So last April the Fed changed the rules and eliminated the six-withdrawal limit on savings accounts. It wrote:

The interim final rule allows depository institutions immediately to suspend enforcement of the six transfer limit and to allow their customers to make an unlimited number of convenient transfers and withdrawals from their savings deposits at a time when financial events associated with the coronavirus pandemic have made such access more urgent.

It was an obvious and nearly risk-free way to help people. Just let them have easier access to their savings.

But it changed the relationship between M1 and M2.

Savings accounts are measured in M2 and left out of M1. But once the six-withdrawal rule was removed, every savings account suddenly became, in the eyes of regulators and people who make these charts, a checking account.

Put M1 and M2 money supply on a graph and you basically see what happened:

The Fundsmith AM also got an inflation question - I feel he correctly distinguishes between the impact on:

fundamentals: this concerns basically the (pricing power) room your portfolio companies might have in terms of gross margin and ROIC

valuation: higher inflation (expectations) might lead to higher rates - which might especially affect assets with higher duration (i.e. equities with a longer tail - often classified as the more growthier stocks and of course long duration bonds on the bond side)

As with many economic topics - you cannot capture inflation in one sentence. But you can of course try to understand what is going on and how it might impact your portfolio companies. On the other hand - if a bit of inflation fear breaks your business model analysis - you have other problems I guess.

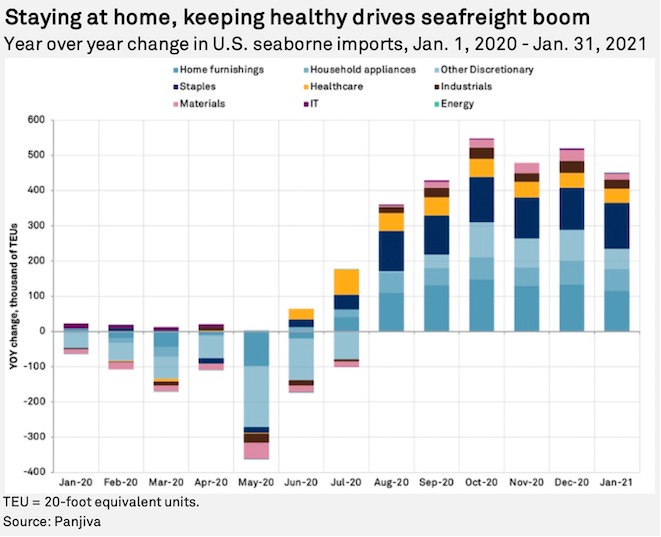

Shipping costs are part of the inflation equation and also a (easy) headline these days. Mid February this year - S&P made a nice summary:

shows that U.S. seaborne imports climbed 20.0% year over year in January, likely including a degree of congestion reduction of vessels that had been delayed in offloading as well as increased demand for goods. Imports of consumer discretionary goods have been the biggest driver of that growth in the absolute number of containers, with growth in household appliances of 80.9% while consumer electronics and home furnishings grew by 17.2% and 34.4%, respectively.

Looking ahead, shipping rates will be driven by a mixture of secular and cyclical factors. On the secular side, increased spending on environmental remediation of the container shipping fleet globally and ongoing investment in expanded infrastructure may keep rates higher for longer.

On the cyclical side, though, demand may decline once pandemic conditions are mitigated by the vaccine — i.e., substitution of services for goods spending — and a clearing of current congestion levels.

There is also a fun graph which wordings are mostly mentioned in conference calls. “Supply chain” and “freight” is winning from “tariffs” lately:

There is also an important note in the end - lacking a bit of data to support it but an important point with regard to impact on inflation:

There are few companies that are willing, however, to commit to pass higher costs through to customers in the form of price hikes either because competitive pressure will not allow it or because of the media relations aspect of price hike commentary.

Similar to commodities: it remains to been seen which costs companies will pass through:

some companies with gross/operating margin room might absorb these costs themselves - or they might have the pricing power to push these costs to end customers (but might not want to do this)

others might not have the room to absorb the higher input costs - doesn’t mean however these type of companies have the necessary pricing power to push these costs onto clients (even if they want to)

And again: this could also just be a temporary blip on the radar.

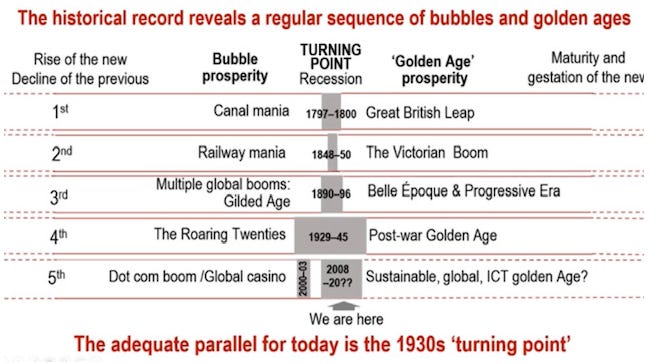

I bumped into this “Paradigm shifts” talk from Carlota Perez on the Baillie Gifford website. Took some screenshots:

Ensemble Capital posted pictures of the Facebook Oculus campus in Seattle. Nearly 10.000 people work in the AR/VR group. Last year Zuckerberg mentioned he expects about 50% of the workforce to work from home longer term - not sure this campus reflects this (don’t know of course how many people will work here).

Enjoy - and feel free to reach out!